by Elizabeth Catte

March 7, 2016

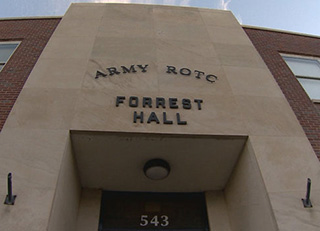

Middle Tennessee State University’s ROTC building, Nathan Bedford Forrest Hall, is named after the Confederate general, slave owner, and first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. The building was named shortly after the Brown v Board of Education (1954) ruling in 1958. The name was an attempt to stall the desegregation of the university which didn’t occur until 1961. Records show students have been actively protesting the name of the building since at least 1968. Before the current movement formed, the last major round of protest against the name began in 2006.

This article was originally published last fall. Since then, the coalition group Change the Name of Nathan Bedford Forrest Hall has organized several protests that have received little attention from campus officials. The only response has been to put together a task force (composed of people overall hostile to the idea of name change) to recommend whether or not the name should stay. Two public meetings have been held by the task force so far. Each meeting has involved community members bringing hostile, racist attitudes towards those students fighting to change the name while student protestors have become increasingly fed up with what they see as a stalling tactic. The second forum a few weeks ago, which featured a heavy police pressence, was shut down for a time by protestors. A third forum is being planned by the task force but it will not be open to the public in the same way, with only “leaders of interested organizations” being allowed to speak during the meeting. The task force is scheduled to make a recommendation in April.

Classes started for the Fall semester this Monday at Middle Tennessee State University, the largest university in Tennessee’s Board of Regents system and my current home. The start of a new semester is still a remarkable thing to me; a time when a fresh start can be exchanged for the price of a little extra patience during morning campus traffic. New beginnings, new students, new traditions.

What never changes, however, is the view from my office: an ordinary parking lot that serves the university’s ROTC building, Forrest Hall, named after CSA General Nathan Bedford Forrest – an individual described by this university’s own Department of Philosophy and Department of History as “deservedly notorious figure,” a “slave trader,” a founder of an “on-going terrorist enterprise,” and “one of the most extreme exemplars of a provincial, exclusionary, and hostile regional identity.” Not only does Forrest Hall carry associations earned by Nathan Bedford Forrest during his own life and of which I am familiar through my work as a historian–a murderer, an abuser of women and breaker of black families, a businessman who earned his fortune buying and selling human beings–it also carries modern associations that the South earned through continued racial oppression in this century. As historian Yoni Appelbaum writes in The Atlantic, the South resurrected its Confederate flags and symbols in the new battle over segregation: beginning in the 1940s, the Confederate flag “was waved at Klan rallies, at White Citizens’ Council meetings, and by those committing horrible acts of violence. And despite the growing range of its meanings in pop culture, as a political symbol, it offered little ambiguity.”

A nationwide call to unburden public institutions of their Confederate symbols in the wake of the unspeakable tragedy in Charleston has reached our corner of Middle Tennessee. Throughout the summer, concerned students, faculty, and alumni have channeled momentum into a campaign to rename Forrest Hall. A public demonstration during the first week of classes generated the letters of support from the Departments of History and Philosophy quoted above, along with a pledge from university President Sidney McPhee to assemble a committee to examine the issue and make a determination regarding the name by April 2016. From local radio station WGNS:

“McPhee said the panel will include student, faculty and community representatives. The panel will be tasked to recommend whether the building should be renamed; retain the name but with added historical perspective; or recommend that no action or change is warranted. The Tennessee Board of Regents would have to approve any recommended name change and the university is also researching whether other state authorities would have to give approval as well.”

The committee will be chaired by historian Derek Frisby, a Civil War scholar at MTSU and member of the MTSU Veterans Memorial Committee.

To be sure, the Tennessee Heritage Protection Act of 2013, which states that any monument on public land erected or dedicated to a historical military figure may not be renamed without government approval, has the potential to make any proposed change to Forrest Hall a complicated or protracted affair. Some students and alumni, however, had hoped for swifter action from the university given the long history of student opposition to the building’s name on campus.

In 2006, an organization under the umbrella Students Against Forrest Hall brought attention to the building’s controversial presence, raising concerns that eventually led to a public response from the university in the form of a town hall meeting hosted by Student Affairs. At that time, President McPhee commented that “This is an opportunity for the community to engage with us in a dialogue about this issue.” Dr. Frisby led the 2006 public forum alongside Tennessee State University history professor Bobby Lovitt. The matter eventually went before the Student Government Association, which initially voted to endorse a name change but later rescinded its support after students produced a counter petition to preserve the name. Campaigns in the 1960s and 1990s also generated support for renaming the building. Although the university declined to make recommendations about Forrest Hall, it did remove other Confederate symbols on campus. The university stopped using Forrest’s likeness as a school mascot in the 1960s, and removed a plaque of Forrest from the student union in the 1990s.

Although the context for new agitation to change the name of Forrest Hall includes an urgency inspired by events in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Charleston–along with a vibrant movement to affirm that #BlackLivesMatter–there is reason to worry that 2015 might be a repeat of 2006 given the university’s favored strategy of “public conversations” and “community engagement.”

Students, alumni, and faculty protest to demand a name change for Forrest Hall.

As a public historian, I am well-versed with and supportive of the power of public engagement, but in order for that to occur we must consider the foundation of these conversations and on which terms we are invited to participate. The appointment of a Civil War scholar and military historian to chair this project–even one as distinguished and capable as Dr. Frisby–sends out a clear signal that we will continue to discuss and debate relics like Forrest Hall in the context of the Civil War and within the arena of military commemoration. If my assumption is correct, it is a context that disadvantages the potential for an open and honest conversation about race and racism on our campus and community.

Instead of debating the merits of Forrest’s military prowess and seeking to define the qualities of manhood and leadership in 1863, we should instead ask why a public institution dedicated a building to a Confederate leader with no association to the university in the year 1954–the year that Brown v. Board of Education signaled the eventual end of school segregation. We must ask why a university founded almost 50 years after the Civil War made the decision to invent a heritage for itself that included a strong but ultimately unearned connection to the Confederacy. The story of Forrest Hall is not a story about Civil War; it is the story about civil rights movement and how universities across the South made conscious decisions about how to project their image into a world unsettled by desegregation and sweeping social change.

I would ask MTSU to heed the recommendations of its own Department of History and sever its extremely public, visible, but also invented connection to Forrest. There are, one estimates, over one hundred public historians at MTSU, from graduate students to world-renowned experts in the field–historians like myself who not only study the events of the past, but also how those events are remembered and politicized in the present. Make use of us, listen to us, but also understand this issue damages our reputations and burdens us with associations we actively work against in our scholarship. Our community, our students, faculty, alumni, and their families, deserve better.

Elizabeth Catte is a Ph.D. candidate in public history at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was originally published on her blog, where she continues to post updates on the campaign.

Comments

One response to “Understanding MTSU’s Forrest Hall Controversy: Think Civil Rights, Not Civil War”

Interesting piece, but I don’t agree with the dichotomy of civil rights and civil war. The question is the overthrow of the 1st Reconstruction. The Brown decision was the beginning of the 2nd Reconstruction. I don’t know the particulars of the MTU situation–is there a Black community around the area, is there a conscious connection between the MTU activists and the struggle to remove a Bedford monument in Memphis. The MTU activists should be saluted, but if the opportunity to broaden and reach out in the area and across the state is there, they should seize it with both hands.

Down with Confederate monuments, Derrick